Scattered across Scotland in various archives lie letters, wills and other documents relating to the lives and experiences of Highlanders who had made the decision to go to the Caribbean at a time when their communities, which were located in Britain’s northernmost region, were convulsing from the aftershocks of Culloden. Culloden, a bloody battle that culminated in the death of between 1,500 and 2,000 Jacobite soldiers near Inverness in 1746, was an important turning point for the Highlands, but there had been many tremors before it to signal that changes were afoot. By the middle of the eighteenth century many people had recognised that what was happening was not, in fact, really about the Highlands or even about Scotland, but a consequence of the larger and more pressing project of building and securing an empire.

Over the course of the eighteenth century, Highland communities, through families, individuals and professional networks, became so entangled with the colonial world that their very survival came to depend upon the connections being forged in the Caribbean. This was the Age of Improvement, a period marked by profound technological change and intellectual development, but for many Highlanders it was also the age of survival. Many hoped that their involvement in the Caribbean would enhance their lives, and those of their families. This was epitomised by people like Thomas Fraser, the author of the opening quotation and a modest entrepreneur from Inverness-shire, whose ventures took him to Grenada and St Vincent. Like countless others, he showed a level of enterprise and ambition that was thought impossible by officials like the commissioners of the annexed estates. These individuals were responsible for managing the lands seized from Jacobites after 1746 and perceived the region as being in a state of perpetual decay. Convinced that Highland geography as well as the ‘indifference – even antipathy – of the people toward innovation’ would forever plague the north and stall development, the government had all but written off the Highlanders’ ability to improve their own situations; to many southerners, they were fit only for military service or wage labour. 2

The imperial environment’s rising profile, especially after 1750, inspires countless questions about how Britain’s more geographically isolated and economically vulnerable regions responded to and collaborated with the process of socio-economic transformation at home. Migration, overseas soldiering and external trade had always been part of the Highland story, but it took on a new meaning in the eighteenth century. It became firmly linked with local development and those who previously had been excluded from positions of authority on account of a deeply entrenched social hierarchy began to assert their influence through initiatives designed to remake society. This article builds upon and expands the important work of pioneers such as Douglas Hamilton, David Alston and Allan Macinnes, who have followed those west-bound Scots by mapping their networks and examining estate investment. It will consider the extent to which the links between the Highlands’ and the Caribbean influenced the development of charitable enterprise at home between c.1750 and c.1820. It begins by considering how the Highland experience fits within the emerging historiography surrounding Scottish slave-ownership before exploring the pivotal importance of the ceded islands, Grenada, the Grenadines, St Vincent, Dominica and Tobago. It was their acquisition from France in 1763 that gave Highlanders the opportunity to really establish a footing in the Caribbean. The final section examines how their activity abroad enabled Highlanders to become involved with and expand charitable enterprise at home by considering the foundation of three academies, Fortrose, Inverness and Tain, and the region’s first hospital, the Northern Infirmary at Inverness. Since all four institutions were seen as having long-term tangible benefits, the perception locally was that the profits of empire were helping to secure the survival of Highland communities.

Establishing roots in the Caribbean

IX. The Most Christian King cedes and guaranties [sic] to his Britannick [sic] Majesty, in full right, the islands of Grenada, and the Grenadines, with the same stipulations in favour of the inhabitants of this colony . . . And the partition of the islands called neutral, is agreed and fixed, so that those of St. Vincent, Dominico, and Tobago, shall remain in full right to Great Britain. 18

Colonies like Barbados and Jamaica were British possessions from 1627 and 1655 respectively, with plantations well established by the middle of the eighteenth century. But it was the territory that Britain acquired after the Seven Years War which afforded an important and somewhat unplanned opportunity for those Highlanders excluded from earlier waves of plantation activity. When Britain first acquired the ceded islands in 1763 the intention had been to confiscate the lands held by the French inhabitants, to survey it and to sell it off to those British planters operating intensive sugar factories in Barbados. Their lack of interest, however, was evident and the commissioners noted that the money, time and energy it would take to transform these islands into profitable enterprises were too much to interest the more established planters. 19 This was worrying since the lack of a planter population threatened to see what cleared land there was ‘fall into total decay’. 20 On the island of St Vincent, where many of the cocoa and coffee plantations had been deserted by the French, and where it was deemed imperative to promote intensive cultivation, the local ‘indian inhabitants’ or ‘Caribs’ were declared ‘altogether uncivilised’ and blamed for impeding useful settlement and cultivation. 21 Enabling as many as possible of the largely Catholic French inhabitants to remain was prioritised and landmark concessions, which included freedom of worship and giving rights to their lands subject to fines and quit rents, were promised to the people of the ceded islands and to Quebec under the terms of the 1763 Treaty of Paris. 22 These were major concessions at a time when strict penal laws remained in force against Catholics in Britain and Ireland, but they achieved results. Many of the ‘new subjects’ stayed, at least initially, and swore the required oaths of allegiance and abjuration to the British Crown. 23 At the same time, land reorganisation and management were also preoccupying many in Britain, but especially in the Highlands, where fierce criticisms were being levelled against the cottar class for their ‘primitive’ land use patterns and perceived lack of civilisation. Clearly, a pattern was emerging of accusing indigenous populations, wherever they were located, of inhibiting progress and development. This pushed many Highlanders out into the empire and some would exploit opportunities in the Caribbean as a way of countering these negative perceptions.

Retaining the French and attracting British planters and labourers from the more peripheral regions like the Highlands to the ceded islands served two distinct, but equally important, purposes, profit and security, although these aims were, as one scholar notes, often contradictory. 24 While some islands, such as St Vincent, Grenada and Carriacou, one of the Grenadines, were economically important because they were conducive to plantations, others, like Dominica, were more important for defensive reasons. 25 To ensure that all the islands became as viable as possible, safe harbours were constructed to facilitate trade and new roads were built to give access to previously inaccessible areas. 26 In many ways, this pattern of development closely resembled what was going on in the Scottish Highlands, where projects focused on constructing roads and bridges, reworking parish boundaries, planning new towns and removing those perceived as being uncivilised, unproductive or rebellious were well underway by the middle of the 1760s. 27 It was a period of profound socio-economic upheaval at home and so the opportunity to go to the Caribbean, to build and run plantations or simply to earn money as labourers or tradesmen, was appealing. While many of those who went already had some kind of connection, usually relatives or friends, others had gained experience in the London or Glasgow merchant houses and had been waiting for the chance to make their move. 28

Grenada, known for intensive sugar and cotton production, was the most attractive of the ceded islands to investors and it is estimated that the number of Europeans there rose from 1,225 in 1763 to 1,661 in 1773. The majority were British, but Highland and Lowland Scots represented twenty-one per cent of all landowners (fifty-seven per cent of British ones) by 1772, and possessed roughly forty per cent of all land planted in sugar and coffee. 29 Planters focused on sugar, which helped the island emerge as Britain’s ‘second leading West Indian colony’ by the mid-1770s. But other islands with sizeable Scottish populations, such as Carriacou, were different. 30 Although its land was fertile, Carriacou’s small size and vulnerability to attack due to the lack of military fortifications made larger British planters wary of investing in sugar. Yet it offered an important opportunity for those eager to break into the Caribbean and by 1790 a mix of large and small cotton farms had emerged in spite of the risks posed by rain, wind and insects. Carriacou was responsible for approximately fourteen per cent of all British West Indian cotton. Scots represented roughly one quarter of the island’s whites and they worked as overseers, carpenters, merchants, clerks, surgeons, constables, fishermen, mariners, masons and tailors. If any had mill experience, they became chief tradesmen. 31 Almost all became slave owners as soon as they could afford to and some of the Highlanders among them are represented in the subscription lists highlighted below.

Family connections, as Douglas Hamilton shows, were critical to the Scottish presence in the Caribbean and resources were often pooled to maximise profits. For most families, from the Urquharts of Aberdeenshire, whose British inheritance money was ploughed into plantations, to Thomas Fraser of Inverness, who had far less available, the Caribbean was a risky venture. 32 Fraser, who accumulated some wealth, had started in Grenada, but settled in St Vincent. It was a difficult road where he saw the dreams of friends evaporate. Writing to his cousin, Simon, a baker in Inverness, Thomas informed him of the fate of a friend:

I told you last year that I have some prospect of making some thing [sic] from my negroes in planting cotton, but the season proved so unfavourable that cotton did not yield anything last year and people did not make one quarter of what they expected . . . I mentioned to you in my last that your friend James Fraser died here some time ago; some little time before his death he quited [sic] the cursed place that ruined him in purse and constitution and died a poor man of a broken heart. 33

By 1798 Fraser had a net worth of roughly £4,020 which included thirty slaves, a number of ‘half slaves’, whom he shared with another cousin, thirty-three acres of land, a house, a ‘negro house’, two horses and five cows. 34 While these were consistent economic gains, they paled in comparison to those of others like Alexander Campbell.

Originally from the isle of Islay, Campbell had gone to Grenada and realised incredible fortunes, but at an enormous cost. 35 Grenada, while the ‘most populous [and] prosperous’ of the ceded islands, was notorious for the vehement anti-Catholicism of the Scottish planters; the tendency of the island’s French planters to leave land undeveloped and to focus on coffee rather than sugar frustrated them. 36 Having first purchased land in Grenada in 1763, Campbell’s interests, profits and net worth ballooned over the next thirty years, but he and others were blind to the consequences. Existing tensions deepened considerably during and after the French occupation of the island between 1779 and 1783 as the Scots tightened their grip on Grenada‘s legislative council which had significant Highland representation. 37 Rebellion erupted in 1795 and when it ended in 1796, the island’s economy had been crippled and many of its leading landowners and legislators, including Campbell, had been killed. 38 While their aggressive business practices had ultimately led to their demise, others were waiting to try their luck. When some semblance of normality resumed after 1796 there was no shortage of Highlanders willing to venture west to Grenada, but also to the newly acquired territories of Berbice and Demerara on South America’s north-east coast. 39

Caribbean investment in the Highlands

Scottish involvement in the Caribbean had a direct impact on the transformation of the Highlands in terms of how its economy was structured, how migration trends developed and the vision of future regional development. The growth of charitable enterprise, in the form of academies, a central hospital and asylum, and through organisations like the Highland societies of London and Edinburgh, was an important component of the transformation. This activity, which began in the late 1770s, suggests a level of engagement with civic development that had not been possible before. Although communal responsibility was not a new concept for the Highlands, it began to be organised in new ways. Highland life and society had formerly been defined by the role of the great chiefs, sustaining and safeguarding the solidarity of the clan structure. By the late eighteenth century, however, traditional expectations about social responsibility had shifted and those beyond traditional elite circles, such as merchants and middling and lower tenant Highlanders, began to experience forms of civic authority. Caught between two worlds, one, wherein social authority rested with the aristocracy and the landed elites, and another, where increased value was being placed on entrepreneurship and cash income, members of this group collaborated with those around them, at home and abroad, to improve the region’s socio-economic prospects.

The foundation of the Highland Society of London in 1778 by twenty-five ‘gentlemen of Scotland’ at the Spring Garden Coffee House reflected the presence of a growing community of Highlanders in the capital. While successive presidents were members of the Highland nobility, its wider membership included merchants, traders, lawyers and physicians in London and abroad and many of them had ties to the Caribbean. 40 Dedicated to development in northern Scotland, in 1786 it established the British Society for Extending the Fisheries and Improving the Sea Coasts of this Kingdom which sought to ‘purchase land and to form free towns, villages and fishing stations in the Highlands’. 41 The growing demand for cured fish in the West Indies, Ireland and Europe as well as the expansion of the re-export trade in sugar and rum encouraged the promotion of a fishery and the construction of harbours. 42 Support for these initiatives came from many of the region’s landowners as well as from the Highland Society of Edinburgh which donated £500. 43 Additionally, the Highland Society of London supported activities that would enhance and protect Highland culture: it led the campaign to produce a Gaelic dictionary; contributed to Inverness Royal Academy; and offered support for the establishment of ‘useful public institutions such as Gaelic schools, the Caledonian Asylum, and Gaelic Chapel in London’. 44 Finding ways of connecting with their culture was, as Sheila Kidd observes, a ‘distinctive response to their colonial experience’. 45 The Highland Society of Edinburgh had similar objectives, but placed more emphasis on ‘giving relief to the indigent, and encouragement to the ingenious among their countrymen’ than on promoting Gaelic, Highland dress or Celtic literature. 46 Support from the London- and Edinburgh-based Highlanders was pivotal, but there was also an overall increase in support for Highland organised initiatives from the diaspora in the Caribbean and elsewhere in places like India and Canada.

A rise in the number of institutions from the late eighteenth century was a direct consequence of this collaboration. Fortrose Academy, Inverness Royal Academy and Tain Royal Academy were opened in 1791, 1792 and 1813 respectively. The Northern Infirmary, the region’s first hospital, was completed in 1804. 47 The impetus for establishing these institutions came largely from the members of the emerging moneyed elite who believed in their practical value. The Northern Infirmary, like hospitals elsewhere in Scotland, would help the sick during periods of distress and reduce the burden on the landowners while the academies would improve the prospects of the youth and lead to greater regional prosperity. 48

Although there were no set rules about where Highlanders went in the Caribbean, and they went everywhere, they tended to congregate on islands where they had connections through family or friends. This meant that certain Highland villages and towns had stronger relationships with some islands than with others. Inverness, for example, which had a more advanced mercantile economy than any other Highland settlement, had numerous links with Jamaica, whereas Fortrose and Tain, with less well developed merchant and business structures, had stronger connections with the ceded islands of Grenada, St Vincent and Carriacou as well as Demerara and Berbice. This is borne out by the subscription lists for each institution which reveal much about migration trends, the influence of existing connections and about who was subscribing. 49 Highlanders supported institutions deemed relevant to the survival of their home region, suggesting an evolving social dynamic that was informing the development of a civil society that would anchor the emerging Scottish and British identities.

As Donald J. Withrington pointed out in a pioneering chapter on educational development in eighteenth-century Scotland, academies were a major innovation. 50 They were fee-charging schools that provided an alternative to the parish schools which had long dominated the region’s educational landscape and enabled pupils to access practical or advanced training locally. 51 The lack of universities in the Highlands, with the nearest in Aberdeen, had stunted the emergence of a multi-level educational culture and encouraged a pattern of out-migration among those who were able and willing to go to university. For those without either the means or desire for this, however, the academies provided the best option for locally based, advanced learning. Between the opening of Tain academy in 1813 and 1837, there was a noticeable decrease in the number of young men going away to university. 52 The local influence of the northern academies was emphasised in Alexander Wood’s Appeal to the Public. Wood, the local minister, was also the Secretary and Vice-President of Fortrose Academy’s Visiting Committee and had worked closely with another local minister, James Smith, and local landed elites, in order to establish the school. 53 While praising the academies for providing practical training to those pupils who were, often for financial reasons, unlikely to attend university, he explained that these schools were pioneering because of their specialist, skills-based teaching.

Not only do they embrace considerably higher objects, but, by affording employment to a greater number of qualified teachers, and, especially, by circumscribing the labours of each, within the limits of that department to which his talents are more peculiarly adapted, they ensure a degree of combined success. 54

What is more, the academies were deemed safer and more respectable learning environments where the ‘advantages of fine air, sea-bathing [and] agreeable walks’ and their perceived shelter from distractions, temptations and vice, appealed to parents who saw education as a path to social advancement. Additionally, the subjects on offer were popular and the emphasis on vocational training was indicative of evolving attitudes about the utility of education. 55 In step with other Scottish academies, students at Fortrose and Inverness took languages such as Latin, Greek, French and English as well as Geography, History (particularly the History of Great Britain) and arithmetic. They also received training in subjects relevant to Britain’s imperial pursuits such as book-keeping, drawing, navigation, spherical navigation, architecture, fortification and gunnery. 56 While being conducive to careers on West Indian plantations, with the East India Company or as officers in the army or Royal Navy, these subjects also supported the changing needs of communities. Town planning, estate reorganisation and management as well as the expansion and construction of roads, bridges and harbours were preoccupying many landowners and government officials at this time and so they were supportive of initiatives that offered young people practical training. 57 The academies were popular from the outset among the aspirational middling class and in 1796 the committee minutes for Inverness Royal Academy recorded that about ‘two hundred students [were] attending different classes’. Many were local, but some, both white and mixed race, had been sent there by their Caribbean-based Scottish fathers. 58

Those leading the committees of subscribers and those occupying the roles of directors of the institutions tended to be the same people and included public officials, such as the provost, baillies and deans of guilds, and a select number of members of the landed and new mercantile elite who had made large financial contributions. In the case of Inverness Royal Academy this was fifty pounds. 59 A major figure in the establishment of both Inverness Royal Academy and the Northern Infirmary was William Inglis, Inverness Provost whose brother, George, was a well-known Demerara planter. William’s efforts were commemorated by a massive inscription carved into the infirmary’s façade that can still be seen today. 60 The aristocracy who were involved gave credibility to the ventures and many, including Francis Humberstone MacKenzie, Lord Seaforth, Lord William Graham, General Sir Hector Munro of Novar, Sir Charles Ross and Sir Gilbert Stirling made sizeable donations. 61 When asking for assistance from Norman MacLeod of McLeod, who had gone to India in 1781 to clear some of his family’s enormous debt, William Mackintosh, provost of Inverness and, for a time, chair of the academy’s committee of subscribers, explained that the academy was ‘most likely to carry into effect the wishes of the greatest part of the Nobility and Gentlemen of the north of Scotland’. 62 MacLeod, whose family seat was Dunvegan Castle on the Isle of Skye, possessed a more obvious social conscience than many of his contemporaries and had been very involved with Friends of the People and had, while a Whig Member of Parliament, supported Catholic relief and the abolition of slavery. 63 Yet great landowners like him faced extraordinary pressure to transform their estates into profitable enterprises and thus understood the need to support educational initiatives designed to inject practical skills into the region. After donating £105 in 1791, MacLeod was appointed to the academy’s committee of subscribers; Francis Humberstone Mackenzie, Lord Seaforth was equally active in the affairs of all three academies, both before and after he left for the Caribbean to become Governor of Barbados and an absentee plantation owner in Berbice. 64

The Northern Infirmary received similar support, although its value was seen in a somewhat different light. As the eighteenth century drew to a close, more emphasis was placed on improvement through collective responsibility and with reference to the infirmary, it was noted that:

It seems reasonable to expect that even those whose circumstances are more limited, the artisan, the labourer, and all who are raised above actual want, should, according to their several abilities, aid an Institution in which they are peculiarly interested, since it is intended exclusively for the relief of such as they; and possible, that some of themselves may one day seek refuge from disease within its walls. 65

While the gentry were keen to reduce their economic burden by encouraging a culture of self-help, the middling ranks looked upon subscriptions as an opportunity to acquire social capital. The subscription committees thus recognised that in addition to local support, the financial contributions from ‘generous Scotsmen in the East and West Indies’, regardless of class, should be sought. 66

The surviving subscription lists for these institutions offer a glimpse at the range of supporters and their locations, and reveal that the infirmary encouraged the broadest support. The Northern Infirmary was the seventh such institution to be constructed in Scotland and linked the Highlands with an emerging culture of improvement through healthcare. The belief that improved health generated prosperity encouraged many to engage with infirmaries as a solution to some of the problems associated with urbanisation. 67 Inverness, while nowhere near as populated as Edinburgh or Glasgow, received many of the people displaced by the clearances. Yet the founders of the Northern Infirmary, such as William Inglis, chair of the committee and town provost, Thomas Gilzean, treasurer as well as a lawyer, local sheriff-substitute, collector of stamp duties and comptroller of customs, and Campbell Mackintosh, whose background is unknown, were particularly bold. Unlike Edinburgh, Glasgow or Aberdeen, Inverness had no local medical school on which to depend for direction and support. 68 Most of the infirmaries in Scotland benefitted in some way from Caribbean money, but the level of direct Caribbean and Indian support for the Northern Infirmary was striking by comparison and perhaps shows the extent to which charitable enterprise relied upon the diaspora. 69 The majority of subscriptions for its establishment came from members of the 75th and 78th regiments in Bombay and Bengal and from individuals in Grenada. An important difference between the subscriptions from the East Indies (India) and the West Indies (Caribbean) was that those from the East tended to come from military companies rather than individuals with purely commercial interests. Links between regiments and other British infirmaries were common, but usually only when a garrison was nearby. 70 What is unique about the regiments subscribing to the Northern Infirmary is that they were stationed abroad and therefore unable to benefit directly from it.

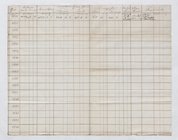

Taken as a whole, the subscription lists reveal the extent of the Highlanders’ imperial reach, showing how many retained links with home and how they connected across the world to support a specific cause. The Northern Infirmary attracted much wider support than the academies and while there is no definitive explanation for this, it is likely that people saw the infirmary as something that would benefit the entire region. Between May 1799 and October 1801, £3,406 had been subscribed to the infirmary which brought the overall total raised to £7,929. There were eighty-three subscriptions from India and most were fifty pounds and over. None of the Caribbean’s ninety-one subscriptions were over thirty-one pounds and most were under five pounds. Martinico and St Kitts appeared to be the most prosperous, with seventeen of the twenty subscribers offering ten or twenty pounds, whereas in Grenada, where there were sixty-four subscriptions, forty-nine were five pounds or less (table 1). 71 These lower subscriptions were probably the result of the Fedon Rebellion which left the Scots there in a state of recovery with little spare cash.

Table 1 Northern Infirmary

A theme uniting all the fundraising campaigns, and resonating throughout Scottish society more generally, was self-help. The details of the subscribers’ names, locations, occasionally occupations and the amounts given reveal significant diversity and there were many people, based in both the Highlands and the Caribbean, who were not wealthy. Highland based people like Simon Fraser, a baker, Alexander MacLeod, a saddler, John Ross, a tailor, and Donald MacBoan, a merchant, who donated five, five, two and one pounds respectively to Inverness Royal Academy between 1787 and 1792, joined those from similar backgrounds in the Caribbean like Dougald McLaughlin, Patrick Miller, James Bremner and Robert Robertson who donated five pounds, five pounds, three pounds and £1 15 s. 3 d. 72

A total of £6,313 was subscribed to Inverness Royal Academy between 1787 and 1796 and significant support, approximately £1,482 (twenty-four per cent of the total), was received from Jamaica (table 2). During this period, only two other donations were received from the Caribbean and both came from the relatives of influential Inverness and Cromarty families: George Inglis, mentioned above, donated ten pounds from Demerara in 1792 and William Alves of St Vincent, George Inglis’ brother-in-law, business partner and probably the son of Dr John Alves of Inverness, one of the committee members, subscribed ten pounds ten shillings in 1794. 73 While the Jamaica figure only relates to a nine year period, it shows that unlike Fortrose and Tain, which developed stronger links with the ceded islands because they lacked the connections needed to penetrate Jamaica, the existing merchant community of Inverness had given it access to the Caribbean economy from an earlier stage. The main fundraiser in Jamaica was Lewis Cuthbert, a native of Castlehill, Inverness, who probably went out there in the hope of regaining some of the wealth and influence that his family seems to have lost over the course of the century. 74 Cuthbert, an attorney and slave trader, first went to Jamaica around 1760 and became the administrator for a number of absentee landowners. 75 Another, far less active collector was Hugh Fraser, a member of one of the prominent Fraser families. In 1788 he had become a member of the Northern Meeting, a selective society established by local gentlemen whose purpose was ‘social intercourse’ and whose initial membership included local landowners, the provost, baillies, lawyers, doctors, merchants and bankers. 76 The role of these collectors was to generate publicity, receive subscriptions and chase late payments; in 1796 there was £204 outstanding from Jamaica. 77 While it is not known how these men became collectors, it is likely that they were persuaded by friends or relatives back home who recognised that it was essential to have collectors of Highland extraction based in the Caribbean, with a commitment to enhancing Highland prosperity.

Table 2 Inverness Royal Academy

The number of donations that Fortrose Academy received from the colonies (table 3) far exceeded the number of ‘local’ British donations, which included those from the counties of Ross and Cromarty, Inverness and Sutherland, as well as from London. As with the Northern Infirmary, support from India was strong and was indicative of a shift in focus from the West to the East Indies, but for Fortrose it was the donations that came from Grenada and the tiny island of Carriacou that were the most revealing. While the individual donations from these places were small, the number of people making them was proportionately greater. According to the school’s register, which includes a list of all subscribers between the institution’s ‘commencement’ in the early 1790s and 1824, a total of £2,679 16 s. 7¾ d. was raised and forty-seven out of the 138 subscribers (thirty-four per cent) were based in Grenada (thirty-six) and Carriacou (eleven). While Grenada’s George Gun Munro, a colonial politician and slave owner, William Scott, occupation unknown, and John McLean, probably a plantation manager, gave twenty-three, fifty-three and twenty-one pounds respectively and Carriacou’s Walter McInnes, a lawyer, gave twelve pounds and William Rutherford, occupation unknown, gave ten pounds, no other subscriptions were more than six pounds and most were under three pounds. 78 Many of these donations had been arranged by the collector, George Gun Munro, in 1811. A native of the Black Isle and former pupil of Fortrose Academy, Munro was a member of both the Highland Society of London and Grenada‘s legislative Council. 79 His extensive networks were invaluable and when submitting the donations, he noted:

The uncommonly handsome manner in which the inhabitants of the island of Carriacou have acted on this occasion. It is one of the Grenadines, dependent on our government: and, with very few exceptions, all the respectable sons of Scotland in it, contributed towards the amelioration, or improvement of so excellent an institution. 80

Further north in Tain, it took ten years to raise sufficient funds to open its Royal Academy in 1810 and according to records compiled in 1819 the total donated between 1800 and 1818 had been £7,666, with £2,062 (twenty-six per cent) coming directly from the Caribbean (table 4). 81 The most generous places were Berbice, Jamaica and Grenada, with collections totalling £576 17 s. 0 d., £262 10 s. 10 d. and £245 0 s. 0 d. respectively. Interestingly, although twenty-nine contributions were made from Berbice and seven from Grenada, just three large donations had come from Jamaica and all were from named individuals. The academy’s Caribbean money was slightly less than the £2,879 that had been raised locally, but one important factor in boosting the local subscriptions was the inclusion of local rates and this was also the case with the Northern Infirmary. Using local rates to support these institutions was a strategic decision at a time when parts of the region were experiencing the height of their clearances. 82 This suggests that local officials were aware of the need to improve the region’s prospects, but what is also evident is the increase in the number of small, individual subscriptions in the amounts of one, two or five pounds. 83 Given that clearances were happening in neighbouring Sutherland, it is likely that at least some of these subscriptions were prompted by a fear of rural collapse. It is unlikely that scholars, without the aid of painstaking genealogical research, will ever be able to demonstrate just how many of these local donations were made possible by direct or indirect Caribbean links, so it must be assumed that such links played a role in at least some of them. Whatever the involvement, the school occupied an important position in the community as noted in the 1845 New Statistical Account:

Table 4 Tain Royal Academy

The Royal Academy, which was built about twenty-five years ago is one of the handsomest and chastest erections in the north of Scotland; and is greatly set off by its fine large play-ground, which has been of late tastefully planted, walled in, and railed. 84

What was also stated was that although a link could not be known for certain, ‘the degrading vices such as drunkenness, appear among the respectable classes to have much decreased’. 85 Subscribing to academies and infirmaries was about more than simply asserting one’s social position; it was about endorsing a particular vision of development. Those who subscribed to these academies were motivated by the belief that they were helping the region and future generations to respond more effectively to the new economic reality at home and abroad. In one of its appeals, the committee for Tain Royal Academy highlighted the institution’s strategic importance and emphasised its pivotal role in reshaping community aspirations by supporting local youth:

Hundreds of our youth who, perhaps, without the means . . . might have sunk into obscurity, have experienced the beneficial effects of the improved plan of education introduced; and a dawn already appears which encourages us to anticipate the cheering prospect of thousands, in generations to come, issuing from this seminary qualified to fill every department in the state, to support the honor and maintain the dignity of the name of Briton! 86

Invoking the term Briton was an important qualifier. At this time, in the neighbouring county of Sutherland, the most notorious phase of its clearances was underway with people being burnt out of their homes to make way for sheep runs. 87 The impression that they were from a different world, one that could not and would not adjust to ‘modern’ Britain caused significant distress, not only among those being forced to leave the lands their people had occupied for centuries, but also among those who felt that they were adjusting and possessed Highland, Scottish and British identities. What troubled them was that despite having long standing and extensive links with Lowland Scotland and with England (particularly London), the Highlands continued to be perceived as a region peripheral to or somehow disconnected from the ‘British’ ideal. The language exhibited in the pamphlet was a corrective which emphasised the fact that Highland and Scottish development were intrinsically linked with the emergence of a broader British identity. 88 In asserting the term Briton, the committee at Tain was demonstrating its connection with a shared identity considered by many within and outside the Highlands to be powerful, progressive and imperially based. That pre-existing national identities of the four nations of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales were the basis of Britain was also emphasised by the Highland Society of London and in its 1813 report, which also highlighted the importance of education, the author explained that ensuring close links with Britain meant protecting local identities:

That it is in the interest of the United Kingdom to keep alive those national, or what, perhaps, may now more properly be called local distinctions of English, Scotch, Irish and Welsh, I think can be proved by reasoning founded upon the first law of nature – I mean self-love . . .

. . . I humbly conceive that the glory of the British Empire may be upheld under the united flag, by keeping alive in its inhabitants the local distinction of English, Scotch, Irish and Welsh, thereby creating a generous emulation between them, which, under the direction of one free and paternal government, many promote the good and glory of the whole. 89

As Britons, these Highland Scots attempted to show how their commitment to the British Empire – their empire – could transcend regionalism. This was at a time, when they, like the Irish, being Celts rather than Saxons, were enduring racial and cultural attacks. While scholars have noted a shared sense of responsibility, based on an appreciation of the region’s military contribution and hospitable culture, it is important to emphasise that Highlanders had been committed to civic culture long before the nineteenth century. 90 This perspective is also borne out by the literature of the academies.

The Sons of the North in every corner of the world are invited to support a seminary calculated to raise their countrymen to a higher pitch of dignified attainment. The Sons and Daughters of Benevolence, from the North, and from the South, from the East and from the West, are solicited to bestow their mite in aid of the children of those “dusky hills,” and tempest beaten vallies [sic] where the hospitable rite was never refused to the stranger, or the destitute – in aid of the Sons of Caledonia, whose heroic deeds have filled the world with admiration and raised their military renown. 91

In spite of the vilification of Highlanders in some quarters, by the 1810s fears of a Jacobite and rebellious north were being replaced with imagined visions of a romantic landscape and valiant people. 92 Highlanders, believing that they were as British as anyone, also endorsed this imagery. Language and literature were central to this construction and when corresponding with James MacPherson, the controversial writer, who claimed to have translated the ancient poems of Ossian in the 1760s, and the Highland Society of London, the committee for Inverness Royal Academy agreed that teaching Gaelic was necessary for ‘cultivating and preserving this original language of our country’. The committee also credited MacPherson, who would, incidentally, encourage many Highlanders to go to India, with drawing wider attention to the region and to Gaelic’s broader importance since it was his ‘elegant translations . . . [which] have rendered it an object of curiosity and attention to the learned’. 93 The committee’s inability to locate a qualified Gaelic teacher, however, in spite of numerous attempts, saw the Society, which often became petulant when things did not go its way, withdraw its support. 94 This suggests a different set of priorities between those members of the Highland diaspora who wanted their home region to grow into the memories they had created, and those on the ground in the north who knew that it could not and perhaps felt that it should not. Reflecting on the profound changes experienced by the region as a whole, Reverend Charles Calder Mackintosh, Minister of Tain, agreed that development had to come, but lamented the loss of language because of what it took from the people’s understanding of themselves:

The most important change, however, seems to be that of language. That from the peculiar station of the highlands of Scotland the change is a necessary one, and that by it the avenues of knowledge are being opened up, and the power of doing good proportionally increased, may readily be allowed; but no Highlander watching the process and its effects can look on it without regret. The stream of traditionary [sic] wisdom descending from our forefathers has been interrupted in its flow; the feelings and the sentiment, will not transfuse themselves into a foreign tongue; and the link of connection between the present and the past generations has been snapped. Before now, the Gael was debarred from fame, because he could speak only an uncultivated though copious and nervous tongue; now he may chance as effectually to be debarred, because the fountain of Highland prejudice and Highland enthusiasm has been checked and rendered turbid at its source, and it may be long ere its inspiring waters renew their ancient flow. Still the change, we have said, is a necessary, and will in the end be a beneficial one; and the sooner, therefore, it be accomplished now, perhaps the better. 95

517 Images

517 Images