James Evan Baillie

We know little of the man as a person, however, we can see from the records that he was a very astute businessman that would not seem out of place in a modern-day big-city financial sector only to be given accolades for his cleaver choices. Only in hindsight, giving the context in which he and his family made financial acquisitions and the period they are set will the modern reader consider possibly branding James Evan Baillie (and his family) as tyrants dealing in the assets of slavery. Maybe today some would even set up a “Nuremberg trial” or a “McCarthy Committee” to pursue their decedents?

Born in 1781, he was the son of Evan Baillie (1742-1835), the merchant of Bristol and Dochfour, Inverness and Mary Gurley (daughter of Peter Gurley of the island of St. Vincent).

James became a London and Bristol merchant and banker (of the firm Baillie, Ames & Baillie), and was a major and astute recipient of slave compensation across the Caribbean.

James is described as thus by Rubinstein: “His family moved from being successful West Indies planters to bankers in Bristol”. 1 This was in 1812 when James had become a partner with his brother, Colonel Hugh Duncan Baillie (of Red Castle and Tarradale), as the two took over the management of the family firm (now ‘Bristol Old Bank’) on the death of his eldest brother Peter.

In 1829 James ‘acquired’ Redland Court mansion (Bristol, England) and 150 acres surrounding farmland from Sir Richard Vaughan, following Vaughan’s bankruptcy. This was because six years earlier Vaughan had mortgaged the estate to their company Elton, Baillie & Co (the Old Bank).

James later became a Member of Parliament (Whig) for Tralee (1813-18) and then in the 1830 Parliamentary elections for Bristol (1830-35), James Baillie and Edward Protheroe both stood for the Whig seat in Bristol (Bristol had two Members of Parliament, and the two seats were divided between the Tory party and the Whig party: voting at this time was not very democratic). Protheroe, whose family were involved in trade with the West Indies, declared himself opposed to slavery. Baillie, also from a West Indian trade family, supported slavery. A number of leaflets were published by both candidates attacking each other and promoting their own views. In the election, Baillie won the Whig seat by 535 votes.

James was a large-scale purchaser of Scottish land, acquiring Glentrome in Badenoch (£7,350) in 1835; Glenelg, Western Highlands (£77,000) in two years later; Glenshiel (£24,500) the following year; and Letterfinlay (£20,000) in 1851.

He appears never to have lived at Redland Court, the occupant being William Edwards, a partner in the Old Bank 1816-52. But he left the Redland estate to his nephews Evan Baillie (of Dochfour) and Henry James Baillie (MP of Elsenham Hall Essex), plus James Leman his attorney as trustees. They sold Redland Court for development and the house is now Redland High School. 2

James lived at 1 Seamore Place, Curzon Street Mayfair both in the 1830s and at his death on 14 Jun 1863. He remained unmarried and died leaving £120,000.

Grenada Plantations

Levera Estate Plantation, St. Patrick’s, Grenada

Levera Estate belonged to a Mr. Snell in April 1785. 3

At a later date Alexander Fraser (1759-1837, of Inchcoulter, Kiltearn, in Rosshire, Scotland) came to Grenada in the late 1790s, he was instrumental in raising money there for the Northern Infirmary in Inverness. In 1806 he purchased his Inchcoulter estate and created the village of Evanton there. Alexander was also a friend of William Smith (of Revolution Hall) and was mentioned in his Will to receive £2000. It is certain that in 1825 Alexander owned plantation Levera Estate.

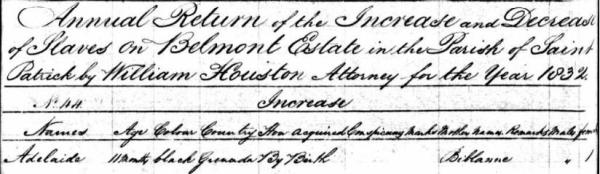

Following the act of 1811 abolishing the slave trade the colonies instituted registers of negroes lawfully held in slavery. A further act of 1819 established an Office for the Registry of Colonial Slaves in London, England. Finally in 1834 slavery was abolished in British colonies and to ensure it effectiveness the act of 1833 provided a sum of £20 million to ‘compensate slave proprietors’. Its distribution was entrusted to a Slave Compensation Commission which began to meet in October 1833 and was terminated at the end of 1842.

On the 9th November 1835 Alexander Fraser (as owner-in-fee) made a contested claim to this Slave Compensation Commission. It was for 94 slaves at Levera Estate for £2759 1s 0d. However a successful counterclaim from Hugh Duncan Baillie, James Evan Baillie and George Henry Ames, all of the City of Bristol, as ‘Assignees for the whole compensation money’. 4

Hermitage Estate Plantation, St. Andrew’s, Grenada

Alexander was also in charge of the Baillie’s plantation Hermitage, and was described, at this time, as a ‘planter of experience’. He was probably also a member of the Grenada Council. He married Evan Baillie’s niece (Emilia Duff of Muirton) ‘some years ago’ and when his son was born in Grenada in 1800/01 the couple named the child Evan Baillie Fraser (1800-91). 5

By 1807 he was regularly described as ‘late of Grenada’ indicating that he was now resident in the UK. In 1812, with the death of Evan Baillie, Alexander Fraser entered into a partnership with Evan Baillie’s third son, James Evan Baillie, trading as JE Baillie, Fraser & Co of London. This company, dissolved in 1820, consisted of James Evan Baillie, Alexander Fraser, Hugh D Baillie, George H Ames and George Fowler. 6

On the 23rd January 1836 a compensation claim was made for 149 slaves at Hermitage Estate, Grenada for £4030 4s 3d by Evan Baillie (who we know was by this time deceased), as trustee on behalf of the proprietors of the Estate.

The previous part-owners were Colin Chisholm (MD of Bristol d.1825) and the Baillie brothers’ father James Baillie (MP of Bedford Square and Ealing Grove, d.1793).

A failed counterclaim was attempted by fishmongerer Rowland Ryley (of 3 Orange Street, Red Lion Square, England), based on a grantee of an annuity of £185 18s, secured by assignment of a legacy bequeathed by the Will of James Baillie Snr. In this case J. H. Forbes acted as agent for the Baillies and secured in their favour. 7

John Sleeper, in 1860, declared “The Hermitage was one of the finest plantations in Grenada. It was pleasantly situated on elevated ground, a few miles from the sea shore, and was the residence of Mr. Houston, a gentleman of great respectability, who was attorney for the for the estate, and also the plantation adjoining, called Belmont.” The previous owner, an Englishman name Bailey (sic) “had spared no expense in stocking the grounds with fruits of various kinds…”. Sadly Houston had the axe freely used to chopped down all of these trees to make way for sugar cane crop. 8

Revolution Estate Plantation, St. John’s, Grenada

The Revolution Hall Estate, at the time overseen by Joseph Barlow, existed during the 1795 ‘insurrection’. It was described in 1845, as “a rich, fertile sugar estate, about two or three miles from the neat looking village or town of Goyave”.

On the 9th May 1836 a claim was made on 168 slaves at Revolution Hall Estate for £4210 16s 8d this belonged to Richard Oliver Smith, owner-in-fee, mortgaged by him on his second marriage. However successful counterclaims by the Baillie brother, as mortgagees and assignees of a legacy of £580 and upwards and his mortgagers back in England for £4105 meant he gained nothing. 9

Richard Oliver Smith (May 1788 – ????) lived n Britain from c. 1793 to 1833. He was the illegitimate son of the Grenada slave-owner William Smith and Sarah Jean (or Dean, then ‘living with’ him) in Grenada.

His father Williams’s Will dated 15 July 1793 (registered 08 November 1794, but with handwritten note on margin ‘proved 30 April 1803’) shows an annuity of £150 later £700 to his lawful wife Elizabeth Smith (with a claus to revoked it if challenges); Sarah Jean was to stay in the house at Revolution Hall, £100 currency immediately, annuity of £150 sterling. £2000 sterling left to pay interest to children ‘being known and called by the descriptions following ‘Mary Smith now in England and Grace Smith in Grenada’, and to Richard Oliver Smith ‘now in England aged 5 years and 2 months’.

He was first married to a Harriet Gee in St Pancras (London, England, 21 August 1806) with whom he had a daughter Emily (b. 1808 Chelsea, Middlesex). Richard divorced Harriet for adultery an on 18 August 1819 married for a second time, to Mary Broderip (daughter of Edmund Broderip), in St. Cuthbert Church, Wells, Somerset, England. They had a daughter, Elizabeth Georgiana (bapt. 1828 Exeter, Devon). 10

A set of accounts for the Revolution Hall Estate exists for the year 1821 (held at the Burke Library, Hamilton College, Clinton, N.Y.) the 50 pages are accompanied by a copy of the conveyance of Revolution Hall to William Smith (dated 1771) and also by copies of letters to William Smith about the unprofitability of the plantation in the years 1832-33. The Account book deals with maintenance, supplies, shipments of rum, and wages and includes lists of slaves on the estate on 31 December 1821, giving name, occupation and age of each. Also lists livestock.

Identified as of Gower Street on 23 July 1822 when he served as trustee for a marriage settlement and on 18 February 1833 a quitclaim appears between Richard Oliver Smith and his fellow trustees (Rogers Weatherall and Francis Broderip) where Richard is ‘released from trusteeship’ to live in West Indies when it appears to have moved to Grenada c. 1833. The couple possibly had a son as well, Richard Joseph Sanderson Smith ( c. 1837 Trinidad), who went on to marry Pauline Josephine Nicholson in Middlesex in 1859. 11

His first daughter Emily Smith went on to marry Rev. John Nurse in Grenada in 1835.

Known Family Relationships – father Evan Baillie (1741-28 Jun 1835), brothers Hugh Duncan Baillie (31 May 1777-21 Jun 1866), first cousins Hugh James Baillie (1786-????), Alexander Baillie (13 Nov 1777-24 Jan 1835), Janet Higgins (née Baillie, 1773-1841), Colin Campbell Lloyd (née Baillie, 1781-1830).

______

Sources

- William D. Rubinstein, Who were the rich? 1860- (Volumes 3 and 4, manuscripts in preparation), reference 1863/2.

- Bristol Record Office 6682/40 for Baillie’s involvement, and deeds of Redland High School purchase.

- Laws of Grenada and the Grenadines: From the Year 1766 to the Year 1852, No.XVII p.48

- Parliamentary Papers p. 99. T71/880: claim 690.

- David Alston, Slaves and Highlanders, http://www.spanglefish.com/slavesandhighlanders/index.asp?pageid=225176.

- London Gazette, thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/17703/page/986, 05/05/1821.

- Parliamentary Papers p. 312. T71/880: claim 701.

- Jack in the Forecastle, John Sherburne Sleeper, 1860, p.342-3.

- Parliamentary Papers p. 312. T71/880: claim 591.

- Familysearch batch no. M51385-3, I01821-5 and C05051-2. Ancestry.com, London, England, Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, 1538-1812

- Settlement, quitclaim and mortgage P89_TRI/130 1822-1835.

![]()